Arranging Haydn's Adagios

John W. Pratt’s engaging article describing the rationale and underlying processes involved in the creation of effective, compelling music arrangements for flute and piano duo, specifically those he has created of a few of Haydn’s Adagios, was published by Flute Focus on July 15, 2012. We have reproduced the article here, with permission from Flute Focus.

=============================================

Arranging Haydn's Adagios for Flute, or Alto Flute, and Piano

Written by John W. Pratt

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), father of the symphony, string quartet, and piano sonata, unfortunately left no known compositions for flute and keyboard duo (see Grove Music Online), although he had a fine appreciation for the flute and used it extensively in his larger ensemble and orchestral works. There is, however, a long and valued tradition of creating transcriptions of Haydn's marvellous music, although fewer are for flute and keyboard than one might hope, and our flute and piano partnership has enjoyed taking up the challenge. We have identified a few wonderful movements that, when carefully and respectfully arranged for this instrumentation, are as effective and delightful as the originals and allow one to hear them when one might never otherwise, or with new ears if one is already familiar with them.

One example is the slow movement of his 24th symphony (1764), a beautiful Adagio for flute solo accompanied by strings, with even a place for a cadenza. Haydn's flute part needs no change, of course, but it was an enjoyable outlet for a would-be composer to write a cadenza based closely on Haydn's material and style, of a length and freedom suitable to a movement standing alone, with only a pianist, not a full orchestra, waiting in admiration. The string parts, however, require not just transcription but significant adaptation to the piano's sonority. For instance, some of the murmuring in octaves by the strings becomes etude-like on the piano, calling for thoughtful selection of which notes to omit in light of the flute part as well as the piano sound. On the other hand, the lower octaves played by the double bass are surprisingly essential, giving the piano an orchestral feel. Interestingly, going down to the low E of the double basses proves to be just right on the piano.

We are fans of the alto flute, and we found that an arrangement of the Adagio from Symphony No.24 for alto flute that is mellower than that for flute, but also extremely beautiful, is obtained by lowering the pitch a minor third. A fourth would allow the alto flute to read the C-flute part directly but feels too low all around. Less than a minor third works for the piano but does not show the alto to greatest advantage.

Haydn wrote many wonderful string quartets throughout his life. His early ones, especially the three sets of six written in 1768–1771 (Opus 9, Opus 17, and the "Sun" quartets Opus 20), are generally considered to have advanced immensely the development of the classical string quartet. The flute can, of course, play the first violin part in string quartets, raising it an octave where necessary and finessing the double stops in some way, but string quartets usually have no need or reason to seek flutes for violin parts. Arrangement for flute and piano obviates this issue, however, and can work well when, for example, the first violin is featured and the other strings support it.

The third movement of Haydn's Opus 20, No. 5, is an Adagio with a simple melody that is treated to delightful filigreed elaboration and obbligato decoration by the first violin. Although more complex string quartet movements may be unsuited to transcription for keyboard and one other instrument, the soloistic nature of the violin part and the simplicity of the lower string parts in this lovely Adagio lend themselves to arrangement for flute and piano. In several passages we found it desirable to raise the violin part an octave to suit the characteristics of the flute, as well, of course, as its range. When the other string parts are transcribed for piano, some octave changes improve the sonic characteristics and help keep the string lines clear, especially where they cross, and partial octave doubling of the melody here and there improves its sound on the piano.

The lowest note available on most alto flutes is the same as the violin's lowest note, so simply transposing the violin part would solve all problems were their characteristics not so different. The third movements of Haydn's Opus 17, No. 1 and Opus 17, No. 2 are both Adagios with gorgeous violin melodies that are harmonized simply by the other three strings. Happily these melodies are equally beautiful on alto flute with very few alterations. When transcribing the other string parts for the piano, octave adjustments are again desirable, for the reasons mentioned earlier. Opus 17, No. 2 also has some passages where we found that the life that strings might add in their way could be supplied most effectively on the piano by further elaboration in the style of Haydn's keyboard music, and it was advantageous to exchange two very high notes for alto flute with the piano a third lower.

With all the music we have played together, from Bach to Walckiers to Martinu to Taktakishvili, these Haydn arrangements for flute and piano are among our favorite repertoire. They are true to the Haydn we revere, yet they also work and are enjoyable for players and audiences alike.

John W. Pratt, May 27, 2012 ©

=========================================

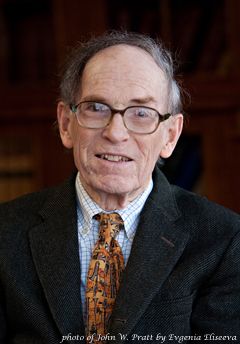

John W. Pratt is a retired Harvard Business School professor and pianist whose transcriptions and arrangements are published by Noteworthy Sheet Music, LLC (click here to view all his catalog listings)